Why spatial intelligence is the missing piece of humanoid robotics

The new humanoid robot NEO from 1X can walk, grasp objects, smile – and is now available for pre-order. For the first time, a humanoid is moving into the living room. But behind the polished hardware lies a simple truth: it does not think for itself. NEO works because somewhere, a human being is watching, correcting, and intervening.

The hardware of humanoid robotics has long been in the fast lane. But the real race for intelligence, understanding, and decision-making skills has only just begun. Because the bodies of these new machines are here – but they don’t yet understand the world in which they move.

The state of affairs: impressive bodies, limited minds

Anyone who visited Automatica 2025 could feel the energy: manufacturers are showcasing their humanoids – this future seems within reach. NEURA Robotics presented its third-generation 4NE1 – with new joints, sensors, and soft skin. At the same time, Schaeffler announced a partnership to deploy several thousand humanoid robots in industrial production by 2035. This is no longer science fiction, but an industrial roadmap.

The prototypes from Agility, Apptronik, and Tesla Optimus are also showing amazing progress in balance, walking motion, and fine motor skills. Hardware is no longer a bottleneck: electric drives, tactile skin, camera arrays, sensor fusion – everything works efficiently, quietly, and scalably. The bottleneck lies elsewhere: in the brain.

Today, even the best robots are still operated in confined environments – they move around in limited production environments, pick up prepared objects, follow scripts, or still receive remote assistance from operators. They move – but they cannot yet move and navigate freely in our world.

The hardware is faster than the brain

This gap between body and mind is becoming the new crucial question in robotics. The leap from a manipulable device to an intelligent agent that understands, plans, and acts in the world requires a new generation of AI systems: spatial intelligence.

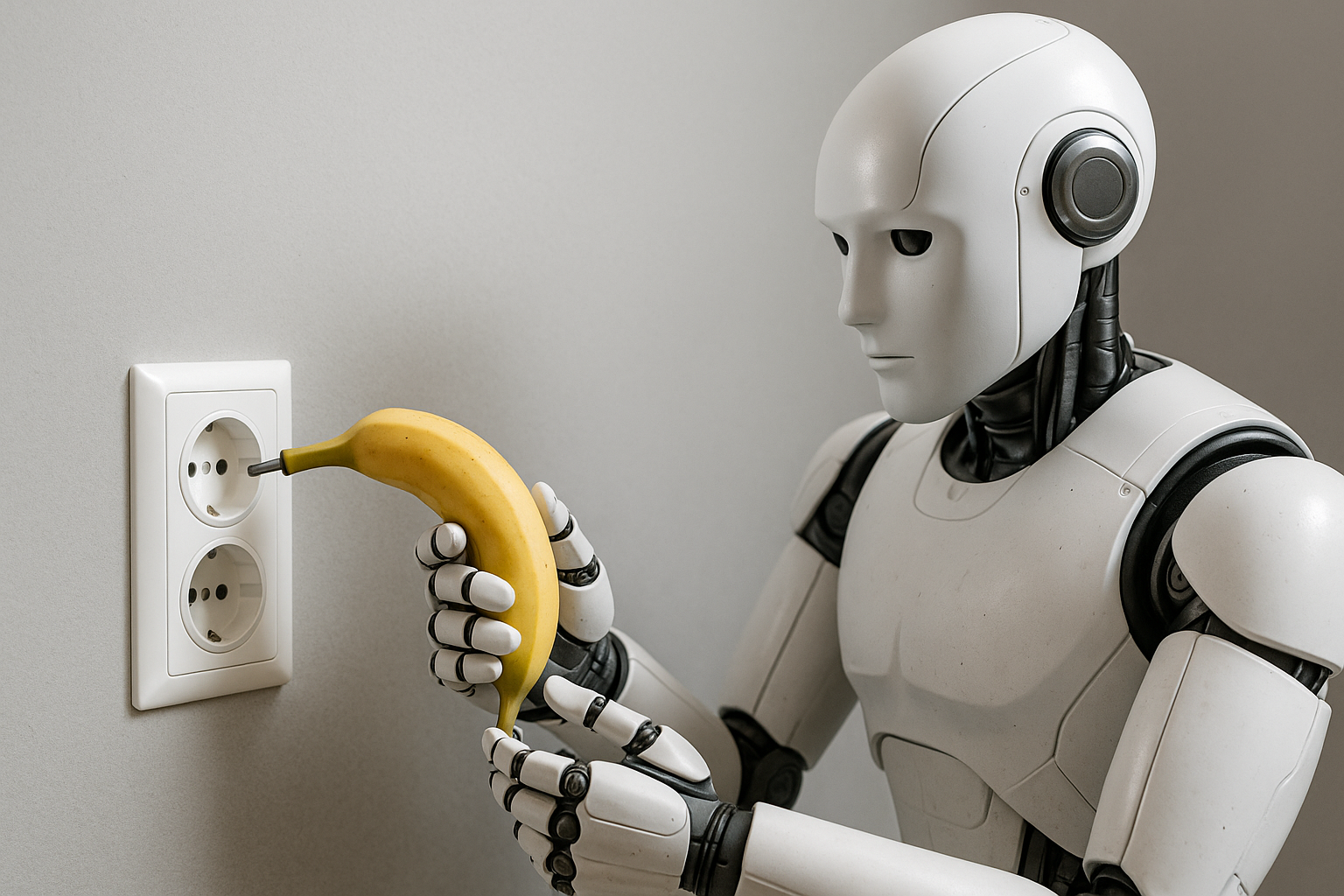

Because what we humans do as a matter of course – orienting ourselves in space, anticipating movements, recognizing objects, understanding causes – is still inaccessible to today’s AI systems. Large language models (LLM) such as GPT or Claude can speak, explain, plan – but they have no body, no space, no physics. They live in text, not in the world.

With LLMs, we simulated the pinnacle of human evolution – language – before we understood the basic functions of the cerebellum. It is precisely this evolutionary sequence that we must now replicate in A

Why humanoids need worldmodels

A humanoid that is supposed to grab a cup, wipe a table, or open a drawer must be able to represent, predict, and update the state of the world.

It must know what is where, what happens when it moves something, and how actions affect the world over time.

This is the task of so-called world models: They map the physical and semantic structure of an environment in a neural memory – including space, movement, causality, and dynamics.

This merges perception (vision), understanding (semantics), and action into a single entity.

Only when machines have such models can they actually learn to think in space – and not just talk about it.

The state of research: The new world builders

This is precisely what research and industry are currently focusing on. Here is an overview:

Fei-Fei Li – “From words to worlds”

The Stanford professor and founder of World Labs calls “spatial intelligence” the next frontier of AI. With her new model Marble, she wants to generate 3D worlds for the first time that remain physically consistent – including objects, depth, and dynamics.

Marble is based on three principles: generative, multimodal, interactive. The model creates virtual spaces, understands language, images, and movement simultaneously, and can simulate actions in these spaces.

The goal is not text comprehension, but world comprehension. Li thus provides the theoretical architecture for what robots will need in the future as an internal world model: a coherent picture of reality in which they can act.

Yann LeCun – “Predicting instead of parroting”

Former Meta chief researcher Yann LeCun is pursuing a different path. His V-JEPA (Video Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture) system is not a generative model, but a predictive one. It learns to predict future states from past observations – in other words, “What happens if…?” LeCun criticizes current generative models as “wordsmiths in the dark”: eloquent, but clueless about physics and causality.

His vision: AI that not only generates content, but understands the world in which it operates.

With V-JEPA 2, Meta is expanding this architecture to include physics-based and sensory representations – a building block for robots that truly understand their environment instead of just describing it.

NVIDIA – “Compute meets world”

NVIDIA combines both strands: With GR00T N1, the open foundation model for robotics, the company links its Omniverse simulation platform, the Isaac training environment, and the new Thor/Jetson hardware generation to form an end-to-end system for embodied AI. GR00T understands images, video, language, and action – vision-language-action (VLA). This creates a scalable training pipeline that links synthetic and real data for spatial learning.

NVIDIA’s strategy is clear: the GPU as the brain of world models – from simulation to robot heads.

Google DeepMind – RT-2

With RT-2, DeepMind has launched an attempt to merge language and image comprehension with robotic action. The model can derive actions from text instructions (“pick up the blue cup”) by translating web knowledge into physical actions. This is an important step, but the transfer from virtual semantics to real dynamics remains unreliable. What works in the lab often collapses in everyday life – precisely where world models need to be robust.

OpenAI – Sora 2 as world simulator

OpenAI’s video model Sora 2 aims to generate physically more consistent and controllable simulations. It is not yet a real world model, but a proto-system that brings together time, movement, and cause and effect. This creates a synthetic training space for robot AI – the virtual sandbox before real engines start up.

Why it’s all so difficult

A world model must simultaneously

- see (3D perception),

- remember (update states),

- understand (link semantics and physics),

- plan (actions in space),

- and learn (from mistakes and feedback).

This integration is more complex than anything LLMs have ever had to do. Language is linear. The world is multidimensional. This makes world models the most complex AI systems ever trained – with an exponential demand for sensors, data, and computing power.

Humanoids need world models – and vice versa

The relationship is symbiotic: humanoids provide the data, world models provide the intelligence. Only through constant feedback from real sensors – camera, depth, force, movement – are the data streams created from which AI learns to think spatially.

Conversely, world models give robots the ability to deal with uncertainty, change, and context. The humanoids of tomorrow will have to learn all these skills gradually. This cannot be achieved by a single provider working through use case after use case on their own. Learning about the world itself must be scaled up.

Where we stand today – and the NEURA shortcut

After decades of pure laboratory research, it has become clear that the bottleneck in humanoid robotics is knowledge – and this knowledge does not come from videos, but from real-world processes. This is exactly where NEURA comes in – and differs from Tesla, Google, OpenAI, or 1X.

While Big Tech relies on large, generalist models, NEURA pursues a domain-oriented, data-driven platform approach.

Instead of universal generalists, NEURA builds specialized workers for clearly defined fields of application, always in collaboration with partners who are specialists in their respective domains. Over the next few months, models will be developed for manufacturing & assembly, logistics & intralogistics, quality control, cleaning & facilities, hospital & laboratory logistics, and service & hospitality.

At NEURA Gyms, 4NE1 learns in real-world scenarios: workpieces, conveyor technology, pallets, hospital equipment, people. Not simulated – real physics in real time. This creates data sets from states, actions, errors, and corrections – exactly what today’s world models are missing.

The plan: in Neuraverse, these abilities are stored and shared as skills. A cleaning pipeline from Stuttgart becomes a module for Zurich or Tokyo, assembly processes become reusable building blocks. Massive scaling via partners makes it possible to find out more quickly which use cases already work in practice and where it is better to wait for more advanced world models.

This is certainly a good plan for making use of the time that Fei-Fei Li, LeCun, and OpenAI need to advance their generic world models.

The road ahead

The future of humanoid robotics will not be decided in the showroom, but rather in the interplay between understanding of the world, data, and industrial reality. The bodies are ready. The brains are emerging. Specific applications are already becoming reality, for example at Neura with its data-centric ecosystem.

We need world models for universal humanoids. Universal humanoids will only become productive when they think spatially, not just act motorically. And they will only become safe when they understand causality, not just execute movements.

We are now where we were with smartphones in 2005 or with the cloud in 2008: the architecture is emerging – now it’s time to decide who will build the operating system of the next decade. The bodies of the humanoids have already been developed. Now the industry is building their brains.