How the collapse of newspapers foreshadows the future of software business models

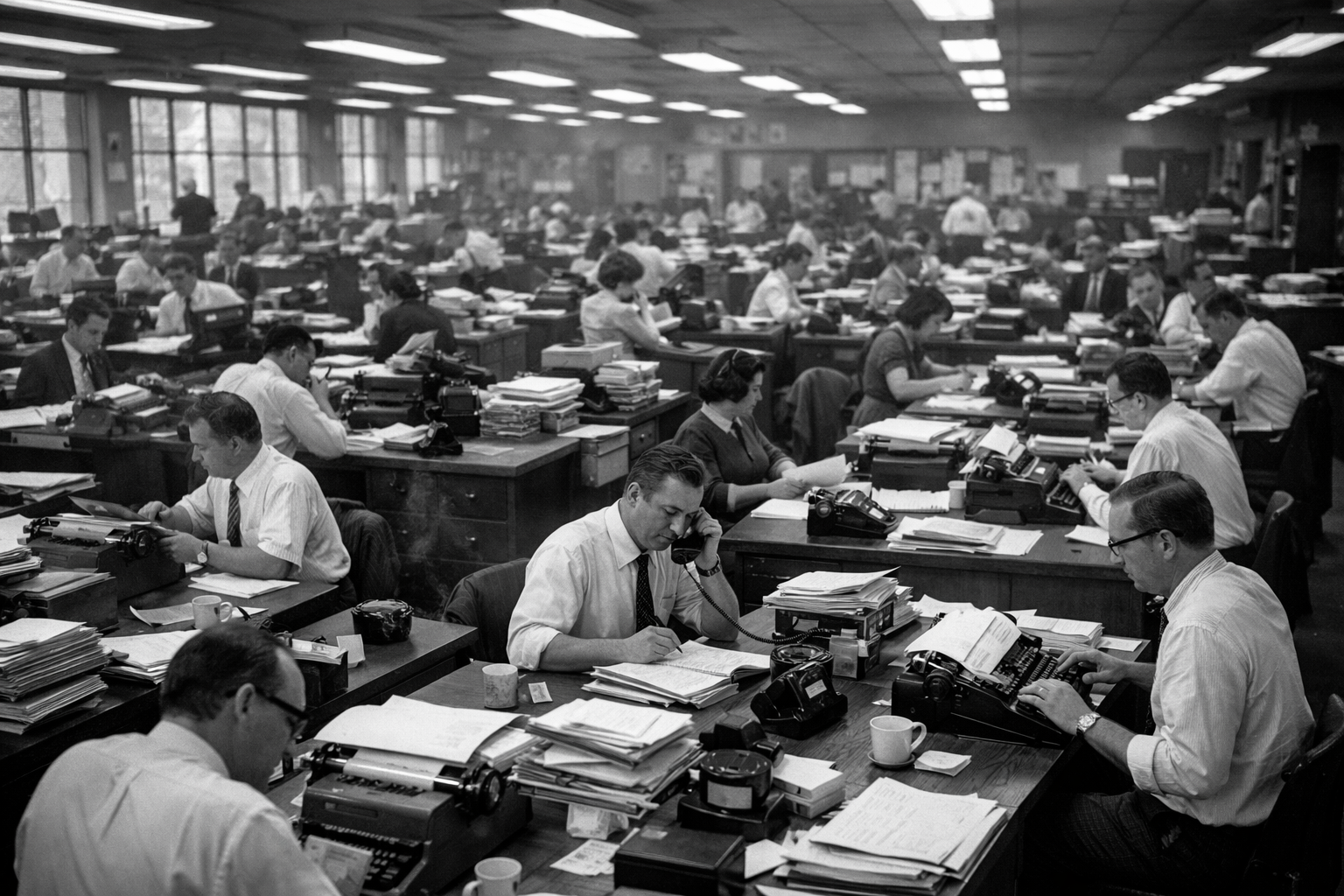

Twenty years ago, the internet hit newspaper publishers. Suddenly, they could reach not just their city, but the entire world. Unlimited distribution. The idea was intoxicating. The reality was devastating.

The problem wasn’t that distribution became free. The problem was that it became free for everyone. A market of scarcity – few could publish because distribution was expensive – became a market of abundance. Power shifted to those who organized content, not those who produced it.

Google won. Between 2000 and 2023, newspaper advertising revenue collapsed by 92 percent. Not because newspapers did worse work. But because the conditions under which value creation happened shifted. Those who produced content no longer controlled distribution. Those who controlled distribution didn’t produce content.

The same thing is happening to software now. Just faster.

Code becomes commodity

Software companies long operated like newspapers. Their key input – code – was scarce and expensive. That scarcity created value. And that scarcity defined who could build software and who couldn’t.

AI-driven code generation makes this input increasingly cheap. What used to take weeks now takes hours. Code is becoming commodity. Not completely. Not immediately. But the direction is clear.

Companies using AI gain an edge. Short term. But this advantage isn’t exclusive. Every software company gets access to the same models. Everyone can suddenly build unlimited amounts of software.

Scarcity becomes abundance. And in abundance, control shifts.

Nobody wants to buy anymore

Software doesn’t die because it becomes obsolete. Software becomes problematic because nobody wants to pay for it anymore.

The logic is simple: Every dollar spent on SaaS licenses is missing somewhere else. And that “somewhere else” is now internal AI usage. Last year, average monthly AI spending by companies rose 36 percent [Source].

At the same time, they reduced their SaaS applications by 18 percent since 2022. Less software spending = more capacity for internal AI.

Companies still need maintenance, support, compliance, integrations. But they want to buy less of it. And pay less for it.

The last decade was defined by growth. You identified a function, built an app, hired a sales team, went public. The pie grew. Everyone could take a slice.

The next decade will be different. The pie gets fought over. Software companies must expand into adjacent areas to justify their existence. Horizontal expansion becomes a survival strategy. Not because it’s strategically smart, but because customers want to pay fewer vendors.

The orderly SaaS silos – one function, one app, one vendor – are breaking apart. What remains is a distribution fight over shrinking budgets.

Who profits? The model providers. They’re the arms dealers of this war. No matter who wins – they make money on all sides.

The identity dilemma

The largest software companies face an additional, existential problem. Their business model is based on human identity.

Take Microsoft. Active Directory connected all Microsoft products through a single identity layer. Every employee had an identity. Every identity had permissions. Every permission linked to products. This enabled the per-seat licensing model: For every user, you pay X dollars per month.

This model works as long as humans are the primary actors in companies. But agents fundamentally change this assumption. The more successful agents become, the fewer human seats exist. An agent doesn’t replace a task – it potentially replaces an entire role. Every replaced role is one license fewer.

Microsoft can’t defend this business model without endangering its future. And it can’t build the future without cannibalizing its business model. There’s no painless path.

This shows up in concrete decisions: In early 2025, Microsoft redirected GPUs meant for Azure customers – into its own Copilot products and internal R&D. The rationale was sound. Its own products have higher margins and better lifetime values than renting compute capacity.

But it reveals something fundamental: Microsoft competes with its own customers. Those who rent capacity get it – unless Microsoft needs it itself. This isn’t malicious. It’s structural. And it’s a pattern.

The crack in the foundation

Hyperscalers seemed unbeatable. Network effects, economies of scale, lock-in. The bigger they got, the stronger they became. That was the theory.

But network effects have limits. And they’re showing now.

The analogy comes from the chip industry of the 1990s. Integrated Device Manufacturers – Intel, Texas Instruments – developed their own chips and operated their own factories. If you wanted chips manufactured as an external company, you could rent capacity. But only as long as they didn’t need the capacity themselves. External orders got pushed when internal production took priority.

TSMC fundamentally changed this model. As a Pure Play Foundry – exclusively chips for others, none of their own – TSMC was neutral. It didn’t compete with its customers. This neutrality became the decisive competitive advantage. Founded in 1987, TSMC controlled over half the global foundry market by 2000. Today it’s over 60 percent.

Today we see the same pattern with compute. Hyperscalers aren’t neutral foundries. They’re Integrated Device Manufacturers. They rent capacity – but use the same capacity for their own products. And when they must choose, they prioritize themselves.

This creates a market gap. For token foundries. Providers who exclusively supply compute capacity without competing with customers. Oracle is already positioning in this direction. Specialized providers will follow.

The insight is simple: Network effects don’t protect you when you become your customers’ competitor. Size stops being an advantage. It becomes ballast.

Room for the new

What’s breaking here isn’t software itself. What’s breaking are the structures the software industry built over the last decade.

Per-seat licensing doesn’t work in a world where agents take over roles. Orderly SaaS silos don’t work in a distribution fight over shrinking budgets. Hyperscaler monopolies on compute don’t work when neutrality becomes a competitive advantage. The illusion of eternal network effects doesn’t work when size creates structural conflicts of interest.

New licensing models will emerge – function-based instead of identity-based. How do you sell software when the buyer has no human users? The answer probably isn’t in seats, but in outcomes. In measurable results, not access.

Neutral token foundries will grow. Companies that don’t build their own agents, don’t sell their own software, but exclusively provide capacity. Their strength will be their neutrality.

Software consolidation will increase. Not through M&A, but through expansion. Who survives will get broader. Function boundaries will blur. This triggers margin fights, which in turn force specialization. A contradiction that unfolds over years.

The publisher era ended with an aggregator that organized the abundance. The software era probably ends without one. Model providers make money on all sides. Hyperscalers compete with their customers. Fragmentation is the pattern, not consolidation.

Conclusion: A new era in software

For entrepreneurs, this means: The giants have structural problems. Their size isn’t just an advantage. It’s also ballast. They have legacy business models to defend. They have customer bases expecting continuity. They have organizational inertia.

Transitions create room. Not for everyone. But for those who stay mobile. Who understand the rules are changing. Who don’t try to play the old game better, but recognize the new rules earlier.

The software era isn’t ending. But it’s reorganizing. And like every reorganization: The established fight their legacy. The mobile find new markets.